« I have a tall cappuccino for John… ». A phrase John hears every morning in his Starbucks in Palo Alto, before jumping in his Tesla to go to work in San Francisco. A routine so natural that John would almost forget that his coffee and his car are the result of an unnatural entrepreneurial strategy: coopetition, a word that combines cooperation and competition.

Anne-Sophie Fernandez, Université de Montpellier; Audrey Rouyre, Montpellier Business School and Paul Chiambaretto, Montpellier Business School

The cup that John inserts into his car’s cup holder is the result of a collaboration between McDonalds et Starbucks, which, although major competitors in the fast food and take-out beverage business, are closely associated in their policy to reduce food packaging waste. Similarly, the Tesla that John drives on California roads is built with many parts and technologies from Tesla’s fierce competitors, such as Daimler or Toyota.

The idea that coopétition, that is, alliances between competing companies, allows for the development of new innovations, is a fairly common one. However, as we explain in a book, summarizing the contributions of coopetition to the simple creation of economic or financial value is reductive. For the last ten years, different works in management sciences have shown how such strategies allow to develop not only economic value, but also societal and environnemental value. Developing the use of these strategies nevertheless seems to require changes in European law.

WHEN SHARING RHYMES WITH EFFICIENCY

Defining what a green innovation is is not always easy and two complementary approaches can be considered: by the product and by the design process.

The first is to apply the label “green” if the product designed is more environmentally friendly than existing products. In this logic, an electric car (like John’s Tesla) can be considered a green innovation since it pollutes less than a car powered by fossil fuels.

Developing a greener product is often a more radical and risky innovation than a non-green innovation. To develop such innovations, the resources and skills of a single company are often not enough. It seems necessary to call upon the expertise of an entire sector. This is how competing companies are led to pool their know-how, their technologies and their knowledge to develop new green standards within their industries.

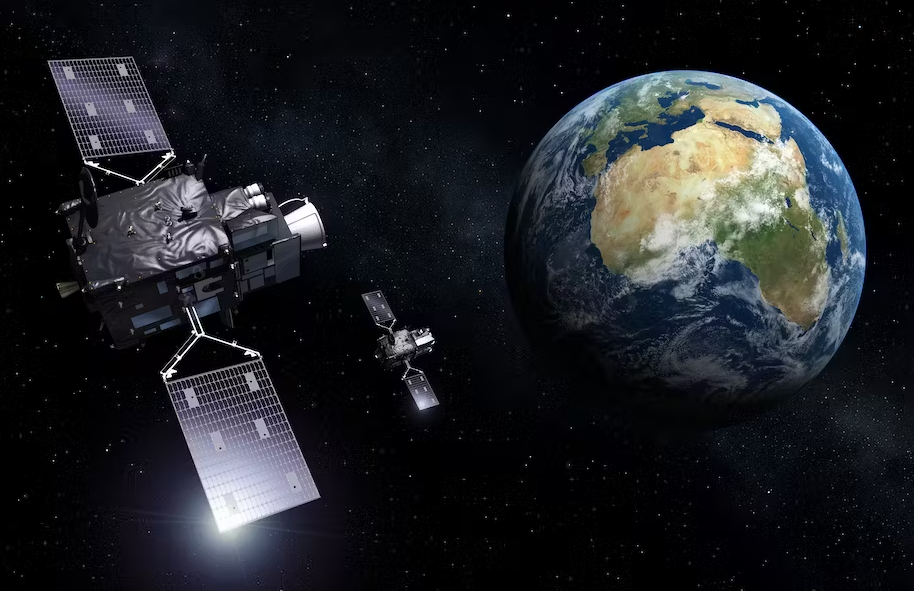

To ensure the ecological transition of the aeronautics industry, for example, eleven competitors, including Airbus, Dassault Aviation and Saab, have joined forces to create the Cleansky network, which comprises 54 companies of all sizes, with the aim of inventing and producing the green aircraft of tomorrow. Also in the aviation sector, CFM International, a joint venture between two competing engine manufacturers, Safran and General Electric, has succeeded in developing jet engines that reduce carbon dioxide emissions by more than 15 percent and nitrogen dioxide emissions by 50 percent. Neither Safran nor General Electric was capable of developing these new green technologies on its own. In the space sector we studied, MTG was developed by the two leading satellite manufacturers, Thales Alenia Space and OHB, to track weather patterns and potentially predict future natural disasters.

The second approach focuses on the process by which the same final product is produced: is it less resource-intensive? A new gasoline or diesel car can, from this perspective, be considered a green innovation if its construction requires less energy or consumes fewer resources than that of competing models.

Pooling competing production or supply chains can also be effective. This was the strategy adopted by Nestlé in the mid-2000s when it cooperated with Pladis, one of its competitors in the United Kingdom, to carry out joint deliveries. Under the slogan “We compete on the shelf, not in the back of a lorry”, the two groups managed to save an average of 28,000 km of deliveries per year, which corresponds to 95,000 liters of fuel and 250 tonnes of CO2.

FOR COMPANIES OF ANY SIZE

It is not only the large groups that are concerned. As we have shown in our work, many start-ups and SMEs join forces with competitors to strengthen their capacity for innovation. Their survival is often at stake because, being smaller, these companies do not always have sufficient resources to develop products and bring them to market.

The same is true for issues related to CSR and the ecological transition. SMEs would like to take up these issues, especially since their customers and stakeholders are increasingly sensitive to them. However, given their limited resources, they often have to make trade-offs that lead them to prioritize their current operational activities to the detriment of their environmental commitments.

Cooperating with competitors can then allow them to have the necessary resources to both continue their activities and commit to a CSR or ecological transition approach. In South Africa, several small competing wineries that did not have the capacity to develop their own bottle recycling system have taken collective action to develop solutions to recycle glass and limit the waste of resources.

Large corporations and SMEs can also interact. For example, Nestlé Waters and Danone, both competitors in beverage distribution, decided in 2017 to join forces and invest in the small California start-up Origin Materials, which develops plastic bottles made entirely from sustainable and renewable resources.

NECESSARY LEGISLATIVE CHANGES

If coopetition is virtuous and allows us to accompany companies in their ecological transition, why don’t we find more companies that engage in this way?

The first reason is the tensions generated by these paradoxical strategies. Indeed, cooperating and competing at the same time generates tensions that are often difficult to ignore. Our study on the space industry suggests that particular attention should be paid to the sharing and protection of information.

Beyond that, there is still some uncertainty as to the legality of these alliances between competitors. Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union considers as “incompatible with the internal market and prohibited all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market.

However, it is not always easy to prove that a coopetition agreement will not restrict or distort competition. When we looked at the real estate sector in Europe, we observed that coopetition strategies can lead to an increase in the price of goods, thus reducing the purchasing power of customers, but bringing more value to sellers.

This is why in the European Union, but also in Australia, regulators are increasingly considering explicit exemptions to prevent competition law from preventing competitors from working together if the agreement helps accelerate the ecological transition of the companies in question.

The balance to be struck between competition law and environmental law remains subtle, however, for example when airlines and their rail competitors join forces. In any case, an evolution of the legal framework seems necessary to accompany a change in the practices of companies in the face of the magnitude of the environmental challenge that awaits them.

Anne-Sophie Fernandez, Maître de conférences HDR en stratégie, Université de Montpellier; Audrey Rouyre, Assistant Professor en Management Stratégique, Montpellier Business School et Paul Chiambaretto, Professeur Associé et directeur de la Chaire Pégase, Montpellier Business School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.